Policy failures drive Nepalis to seek their fortunes abroad

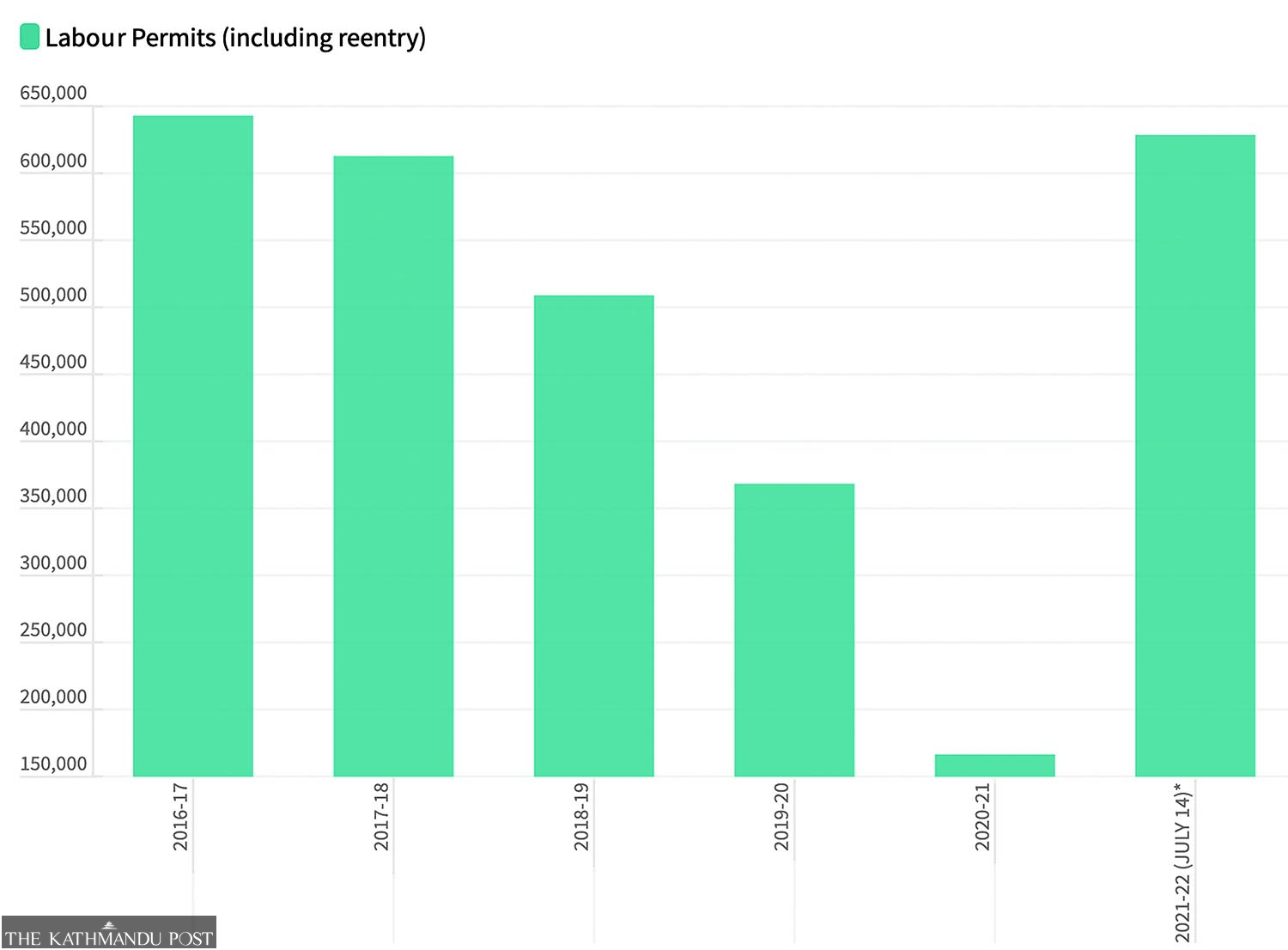

In the last fiscal year, more than 628,503 people received labour permits, the second highest number on record.

KATHMANDU: Young Nepalis can’t wait to get out of the country for high-paying jobs abroad despite the economic and agricultural potential in the country, experts said.

With skilled workers jetting off to foreign lands en masse, the country has been left with an ageing population, and attempts to lure them back do not seem to be working.

Migrant departures had stopped briefly due to COVID-19, but the exodus is now back to pre-pandemic levels. More than 1,700 young Nepalis are leaving the country daily to work abroad, as per official figures.

In the last fiscal year ended July 16, more than 628,503 people received labour permits, the second highest number on record, according to government statistics. The figure excludes young people leaving the country for higher education.

Experts and economists attribute the mass departure to stagflation where the economic growth rate slumps and unemployment rates surge.

“Around 500,000 Nepali youths are estimated to enter the labour market every year,” said Jeevan Baniya, assistant director at the Centre for Study of Labour and Mobility, Social Science Baha, a non-profit organisation involved in research in the social sciences in Nepal.

“Around 400,000 of them go for foreign employment.”

With the Covid crisis receding, there has been an increased demand for labour worldwide. “As the country cannot assure decent work for youths and invest in their skills, the numbers keep surging,” said Baniya.

After decades of political instability, the 2017 elections produced a government with a clear majority. People had high hopes; but the government, true to Nepali tradition, didn’t last long.

Experts say that political uncertainty is back, and as a result, people are leaving the country in hordes.

“The figure is alarming,” said Thaneshwar Bhusal, under-secretary at the Foreign Employment Management Section under the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security. “In the absence of decent job opportunities at home, people are leaving for foreign countries in droves.”

Bhusal underscores the need for a long-term policy. “In recent years, we have realised that the workforce cannot be retained through employment alone. We need to focus on entrepreneurship.”

Though successive governments have presented various plans to help entrepreneurship, they have remained on paper.

The government has been unveiling youth programmes to promote entrepreneurship almost annually, but none of them has been implemented, said the Auditor General’s report published recently.

Nepal’s economy saw a negative growth of 2.1 percent in the fiscal year 2019-20 largely due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

With politics back to its customary fluctuation, the country has not been able to revive the economy hammered by the coronavirus outbreak, economists say. Then the world economy encountered a new enemy—inflation.

Households that have recently escaped poverty could be pushed back into it by rising inflation. Some experts say that growing poverty due to rising prices is one of the key factors behind Nepalis jumping into the foreign labour market.

“Government policies lack clarity,” economist Bishwambher Pyakuryal told the Post recently. “Despite the allocation of a large budget for entrepreneurship every year, it has benefited only a few.”

In the last fiscal year, the government issued two budget statements one after another followed by one budget revision. This resulted in one of the lowest capital expenditures in many years. The government was able to spend only half of the capital budget.

Capital expenditure is the money spent by the government on the development of infrastructure. The spending would create jobs.

Political uncertainty has been the key factor forcing young people to go abroad, experts say.

According to the Department of Foreign Employment, the number of Nepalis working abroad surged after 2000 when the Maoist insurgency that started in 1996 reached its peak.

In the fiscal year 2000-01, just over 55,000 Nepalis went abroad. They sent home a little over Rs47 billion in remittances. With the country’s economy suffering due to the insurgency, Nepali youths had no choice.

From just 3,605 migrant workers who received work permits in 1993-94, the number started to multiply, reaching as high as 527,814 individuals in 2013-14, swelling by nearly 147 times in two decades.

Remittances too jumped by more than 11 times, reaching Rs543.29 billion in the same period. According to the Department of Foreign Employment, it issued labour permits to more than 5 million Nepalis in the last two decades.

The number started to drop after the government started tightening the labour sector amid reports of workers being abused in many labour destinations. In 2018-19, a year before the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of hopeful migrants receiving labour permits fell to 508,828.

In the last fiscal year 2020-21, the figure plunged to a 16-year low. Despite the drop in migrant worker numbers, remittances kept soaring.

The central bank’s report says that one of Nepal’s major exports is labour, and most rural households now rely on at least one member’s earnings from employment away from home.

Nepali workers have sought foreign employment as both agricultural and non-agricultural sectors have been struggling to generate new employment opportunities.

With limited arable land, landlessness is pervasive; and the number of landless households has steadily increased in the farm sector.

In the non-agricultural sector, the slowdown in growth, especially since 2000-01, due to the Maoist insurgency which killed more than 17,000 people, further retarded the pace of employment creation, the report said.

Political unrest in the country adversely affected economic growth.

According to the central bank, for most of the past decade, the economic growth rate hovered around a mere 3-4 percent, peaking at 6 percent in fiscal 2007-08, following the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Accord between the Maoists and the government.

Immediately after that, long hours of darkness became the routine as the country entered a period of severe power shortages. Between 2007 and 2017, the massive electricity supply shortage caused up to 18 hours of rolling blackouts daily.

This load-shedding had a dire effect on Nepal’s economy. According to a World Bank report, reliable power supply would have increased the country’s annual gross domestic product by almost 7 percent, and annual investment would have been 48 percent higher.

Load-shedding became another push factor for young Nepalis to go abroad.

“The number of Nepalis going for foreign employment in the last fiscal year 2021-22 was the highest in the past five years,” said Shesh Narayan Poudel, the director general at the Department of Foreign Employment.

Baniya said that the resumption of labour migration to Malaysia, which had stalled from 2018 to 2019, might have contributed to the increase in departures. “The figure might be small, but it has made some contribution.”

The Nepal government had barred Nepali workers from going to Malaysia, which was the top destination for years, following a crackdown against agencies charging hefty fees from Nepali workers for pre-departure services.

Labour migration to the Southeast Asian country resumed in September 2019 after the two governments signed a new labour deal.

“Lack of job opportunities in the domestic labour market has been the main reason for foreign labour migration for a long time,” Baniya said.

“Salaries in Nepal are not enough to support a family. Most of the jobs available in the country do not guarantee social security,” Baniya said. “The government and other stakeholders need to improve the condition of the domestic labour market.”

The remittance sent home by migrant workers has become the backbone of Nepal’s economy over the years. Remittance inflows amounted to Rs904.1 billion in the first 11 months of the last fiscal year ended mid-June, according to central bank data.

“The government needs to invest in the development of skills and creation of jobs in order to decrease our reliance on remittance,” said Puskar Bajracharya, economist and professor at the School of Management, Tribhuvan University.

“The government and the authorities concerned failed to create employment opportunities at home. A massive labour force from the agricultural sector has shifted to other sectors over the years, but they could not be absorbed in other sectors in the absence of adequate opportunities,” said Bajracharya.

“Global demand for migrant labour has increased with an increment in economic activities after the easing of Covid restrictions and lockdowns,” Bajracharya added.

Government reports show that there is pent-up demand for skilled workers too, particularly caregivers and nurses.

“For young Nepali people, there are lots of opportunities abroad. They will keep leaving in droves,” said Bajracharya.

-Kathmandu Post