Bihar: Their son vanished – then an imposter took over for 41 years

In February 1977, a teenage boy disappeared on his way home from school in the eastern state of Bihar.

KATHMANDU: A court in India has sent to prison a man who was found guilty of posing as the son of a wealthy landlord for 41 years. The BBC’s Soutik Biswas pieces together a gripping tale of deceit and delay in justice.

In February 1977, a teenage boy disappeared on his way home from school in the eastern state of Bihar.

Kanhaiya Singh, the only son of an affluent and influential zamindar (landlord) in the Nalanda district, was returning from the second day of exams. His family lodged a “missing person report” with the police.

Efforts to find Kanhaiya came to naught. His ageing father slid into depression and began visiting quacks. A village shaman told him his son was alive and would “appear” soon.

In September 1981, a man in his early 20s arrived in a village, barely 15km (9 miles) from where Kanhaiya lived.

He was dressed in saffron and said he sang songs and begged for a living. He told the locals that he was the “son of a prominent person” of Murgawan, the missing boy’s village.

What happened next is not entirely clear. But what is known is that when rumors that his missing son had returned reached Kameshwar Singh, he traveled to the village to see for himself.

Some of his neighbors who had accompanied Singh told him that the man was indeed his son and he took him home.

“My eyes are failing and I can’t see him properly. If you say he is my son, I will keep him,” Singh told the men, according to police records.

Four days later, news of her son’s return reached Singh’s wife, Ramsakhi Devi, who was visiting the state capital, Patna, with her daughter, Vidya. She rushed back to the village and, on arrival, realized that the man was not her son.

Kanhaiya, she said, had a “cut mark on the left side of his head”, which was missing in this man. He also failed to recognize a teacher from the boy’s school. But Singh was convinced that the man was their son.

Days after the incident, Ramsakhi Devi filed a case of impersonation and the man was arrested briefly and spent a month in jail before securing bail.

What happened over the next four decades is a chilling tale of deception in which a man pretended to be the missing son of the landlord and inveigled himself into his house.

Even as he was on bail, he assumed a new identity, went to college, got married, raised a family and secured multiple fake identities.

Using these IDs, he voted, paid taxes, gave biometrics for a national identity card, got a gun licence and sold 37 acres of Singh’s property.

He steadfastly refused to provide a DNA sample to match with the landlord’s daughter to prove that they were siblings. And in a move that stunned the court, he even tried to “kill” his original identity with a fake death certificate.

The imposter’s tale is a grim commentary on official incompetence and India’s snail-paced judiciary: nearly 50 million cases are pending in the country’s courts and more than 180,000 of them have been pending for more than 30 years.

In official records, the man is curiously registered as Kanhaiya Ji – an Indian honorific. A first and second name is a universally accepted form of identification.

Except, according to the judges who found the man guilty of impersonation, cheating and conspiracy and sent him to prison for seven years, his real name was Dayanand Gosain, who hailed from a village in Jamui district, some 100km (62 miles) away from his “adopted” home.

A black-and-white photograph of Dayanand Gosain from his wedding in 1982 – a year after he entered the Singh household – shows a fair man with a thin mustache. He is wearing a flimsy decorative veil and staring into the distance.

Much of the facts about him before he entered the Singh household are fuzzy.

His official documents have different dates of birth – it’s January 1966 in his high school records, February 1960 in his national identity card and 1965 in his voter identity card. A 2009 local government card for accessing food rations listed his age as 45 years, which would mean he was born in 1964. Gosain’s family said he was “about 62”, which would tally with his birth date in the national card.

What investigators could confirm was that Gosain was the youngest of four sons of a farmer in Jamui, that he sang and begged for a living and that he left his home in 1981. Chittaranjan Kumar, a senior police officer in Jamui, says Gosain married early, but his wife left him soon after.

“The couple didn’t have children and his first wife remarried and settled down,” says Mr Kumar. He also tracked down a man in the village who had identified Gosain in the court during the case. “It was fairly well known in his native village that Gosain was living with a landlord’s family in Nalanda,” Judge Manvendra Mishra wrote in his verdict.

Singh got Gosain married off to a woman of his own landowning caste a year after taking him home. According to a document available with the family, Gosain pursued a bachelor’s degree in English, politics and philosophy at a local college, which found his conduct “satisfactory”.

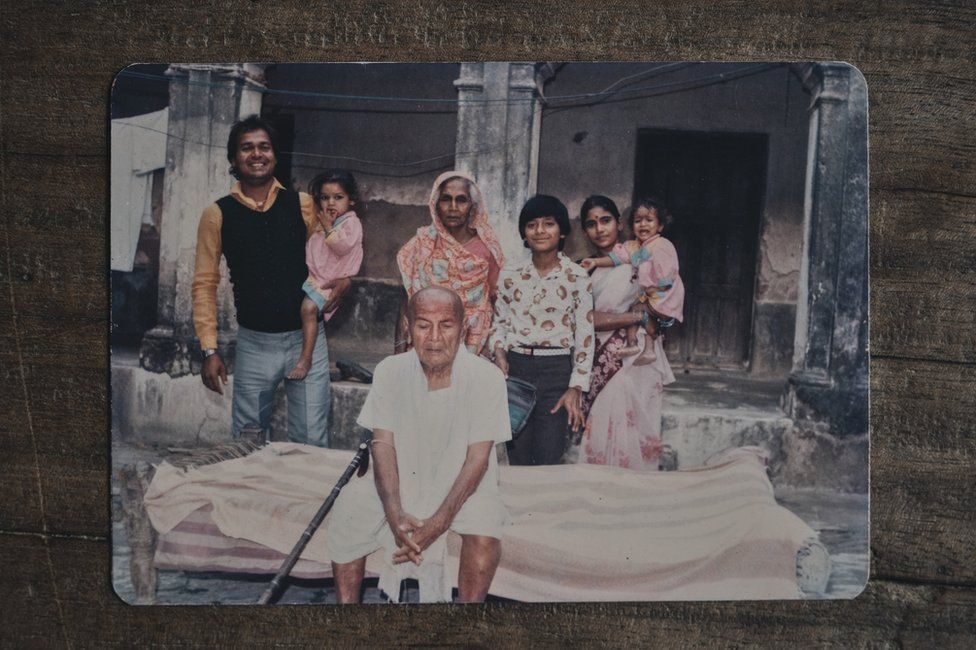

Over the years, Gosain had two sons and three daughters. After Singh’s death, he inherited half of a nearly century-old, two-storey mansion in Murgawan. (The other half partitioned by a low wall belongs to another branch of Singh’s family.)

Overlooking a large water tank, ringed by mango and guava trees, and secured by an unpainted iron gate and brick walls, the house has a decaying air about it. With three generations living under its roof, the 16-room house would have once thrummed with life.

Now there’s an eerie quietness about the place. The courtyard is unkempt, and a rotting wheat hulling machine lies in a corner.

Gosain’s elder son Gautam Kumar said his father generally stayed at home and managed some 30 acres of farmland. The land yielded rice, wheat and pulses, and was mostly farmed by contract workers.

Mr Kumar said the family had never discussed the “impersonation case” with his father.

“He is our father. If my grandfather had accepted him as his son, who are we to question him? How can you not trust your father?” he asked.

“Now after all these years, our lives and identities are hanging in balance because my father’s identity has been taken away. We live in so much anxiety.”

In court, Gosain was asked by Judge Mishra where he had lived and with whom during the four years, he went missing.

Gosain was evasive in his replies. He told the judge that he had stayed with a holy man in his ashram in Gorakhpur, a city in the neighboring state of Uttar Pradesh. But he could not provide any witnesses to back up his claim.

Gosain also told the judges that he had never claimed to be the landlord’s lost son. He said Singh only “accepted me as his son and took me home”.

“I did not deceive anyone by impersonation. I am Kanhaiya,” he said.

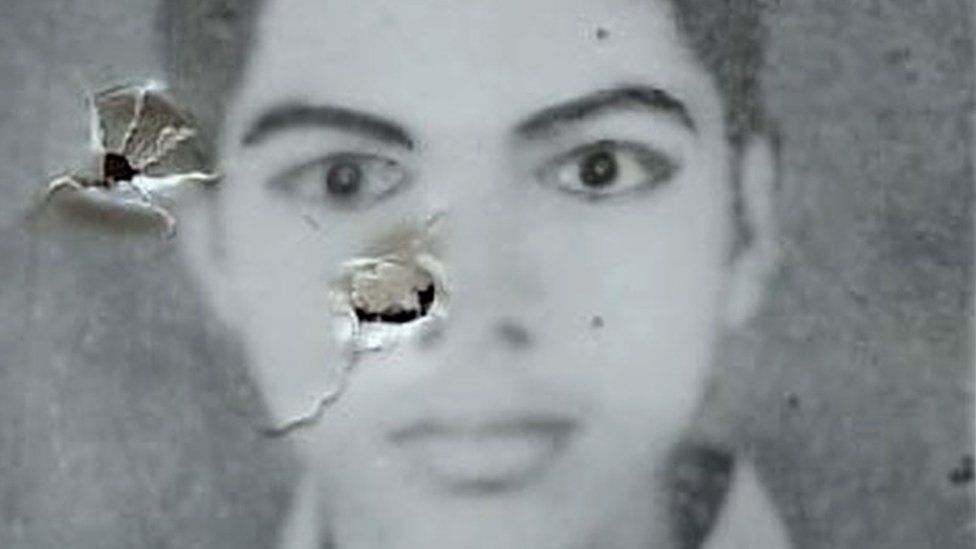

In his only existing photograph – a black and white studio mugshot, mutilated by stapler pins in court papers – Kanhaiya Singh, with his neatly parted hair and wearing a light-color shirt, peers into the camera.

The irony is that Kanhaiya, who was 16 when he vanished, has been all but forgotten in Murgawan, a sleepy village of around 1,500 mostly upper-caste Hindus some 100km away from Patna.

Gopal Singh, a senior Supreme Court lawyer and a relative, remembers Kanhaiya as a “timid, shy and amiable” boy. “We grew up together, we used to play together. When he disappeared, there was a hue and cry,” he said. “And when the man appeared four years later, he didn’t resemble Kanhaiya at all. But his father was insistent that he was his lost son. So what could we do?”

Kameshwar Singh, who died in 1991, was an influential landlord, owning, by one estimate, more than 60 acres of land.

He was an elected village council leader for close to four decades and counted Supreme Court lawyers and a member of parliament among his close relatives.

Singh had seven daughters and a son (Kanhaiya) from two marriages – the boy was the youngest and, by all accounts, his favorite child and natural heir. Interestingly, the ailing landlord never went to court and defended Gosain.

“I had told the villagers,” Singh told the police, “that if we find this man is not my son, we will return him.”

The case was heard over four decades by at least a dozen judges. Finally, a trial court held the hearings without a break for 44 days beginning in February this year and gave its verdict in early April.

Judge Mishra found Gosain guilty. In June, a higher court upheld the order and imposed seven years of “rigorous imprisonment” on Gosain.

The court found all the seven defence witnesses unreliable. “We never took this case seriously. We should have gathered our evidence better. We never thought there was any doubt about my father’s identity,” said Gautam Kumar.

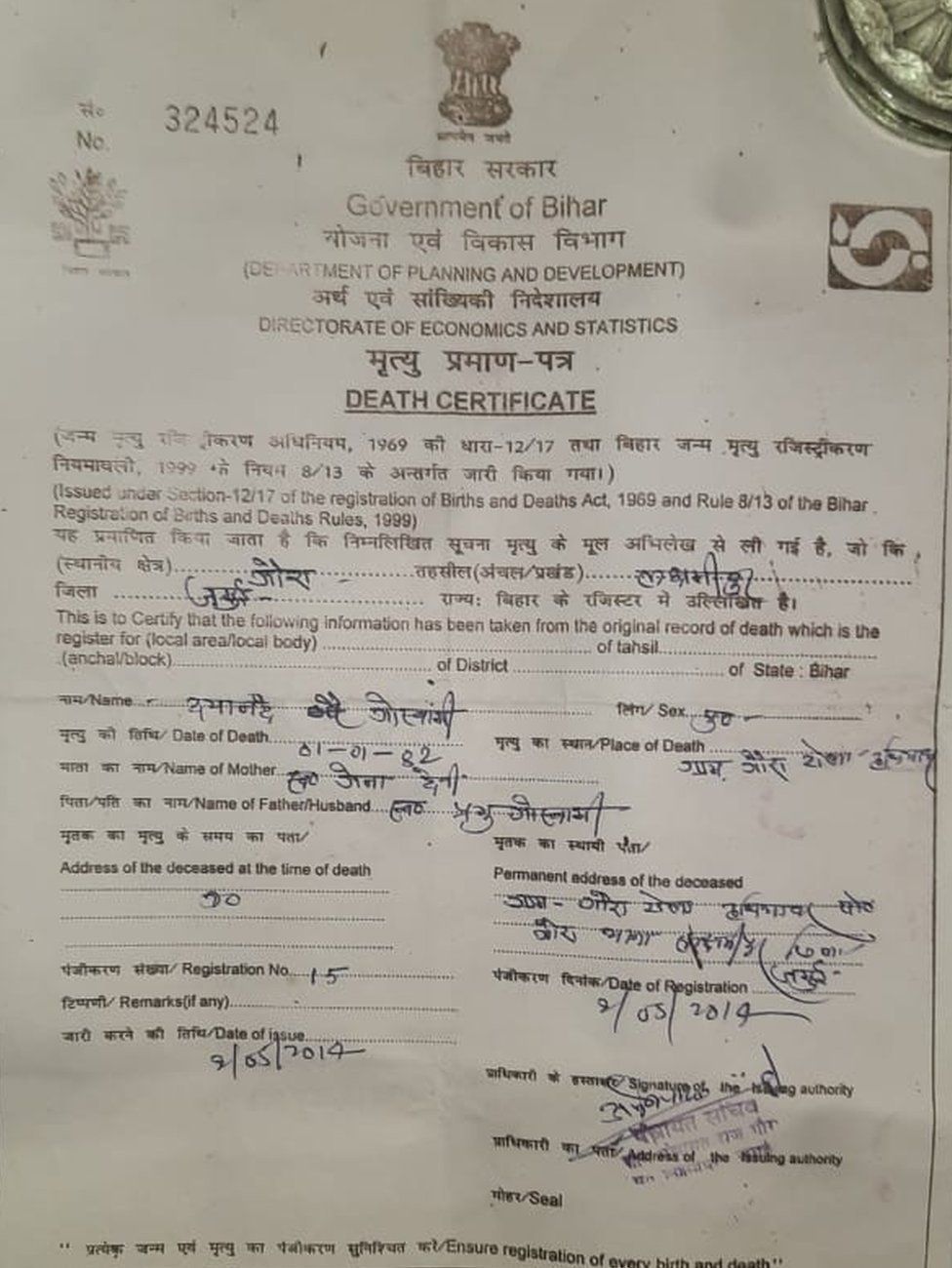

The drama in the court climaxed with the defence producing a death certificate, declaring Dayanand Gosain was dead.

But the certificate was riddled with inconsistencies. It was dated May 2014 but said that Gosain had died in January 1982.

Police officer Chittaranjan Kumar says when he checked local records, he found no record of Gosain’s death. Local officials told him the certificate was “obviously fake”. Mr Kumar said: “It is very easy to get forged documents here.”

The court asked the defence why a death certificate was made 32 years after the death of the person and dismissed it as a forgery.

“To prove himself as Kanhaiya, Gosain killed himself,” said Judge Mishra.

The clinching evidence against Gosain was his refusal to give a DNA sample, which the prosecution first sought in 2014. For eight years, he stonewalled and only this February, gave a written statement refusing to give his sample.

“No other evidence is now needed,” the court said. “The accused knows that a DNA test would expose his false claim.”

“The burden of proof lies on the accused to prove his identity,” the judge added.

Gosain’s conviction could be the tip of the proverbial iceberg, lawyers say.

The court believed there was a wider conspiracy involving several people of Murgawan who had helped “plant” Gosain into Singh’s family as his lost son.

The judge suspected that these people could have bought land owned by Singh and later sold by Gosain as his natural heir. Both the claims have yet to be investigated.

“There was a huge conspiracy hatched against my family [to grab] our property, taking advantage of my husband’s ill health and failing eyesight,” Ramsakhi Devi, who died in 1995, told the court.

There are still many unanswered questions in this story of deception and duplicity.

What happens to the land sold by Singh using a fake identity? Will the plots be taken back from the buyers and distributed among his surviving daughters who are the natural heirs? How will Gosain’s fake identities be dealt with?

And most importantly, where is Kanhaiya?

Under Indian law, a person missing for more than seven years is assumed dead.

Why has the police not closed the case? Is he alive?

-BBC